Gone Home is a classic of the “walking sim” genre and has also been the centre (or at least part of) a number of debates, right down to “What even is a video game, and is this one?” It was also in the unenviable position of being a target of the anti-woke brigade of the time (it came out in 2013), the angry tendrils of which became GamerGate just a year or so later.

I think it’s probably impossible to discuss Gone Home, at least how I want to, without spoilers, so consider this your warning. It has been out for over a decade now, so what’s your excuse anyway?

Despite telling a familiar story, Gone Home is a subversion in almost every other significant way. The first main way it subverts expectations is that it is not about the player character. The character you play as is Kaitlin Greenbriar, newly returned from a year abroad, but the story isn’t about you. Your younger sister Sam is the star of the story, with your mum and dad as secondary characters. Your year in Europe doesn’t matter at all – all we learn about that is a handful of postcards scattered across the house, and what we discover about Katie aren’t the things that make you hold a game character in your heart long after the fact.

We pick up as Katie (as she is known to her family) arrives home fresh off her trip to Europe in the summer of 1995. It was a short-notice flight, so her parents aren’t home to greet her – they are away for an anniversary trip. Sam is meant to be there to welcome her home, but you soon discover that the house is empty. In fact, you are greeted by a note on the door from Sam, warning you not to try to find her.

What follows is about two hours of exploring your family’s new home that they moved into while you were away. It’s very much as though the team at The Fulbright Company wanted to make a demo reel of the power of environmental storytelling. There’s no traditional narrative aside from a few diary entries narrated by Sam as you find various items, you’re just expected to piece together what’s going on through the objects in the home. Letters, appointment slips, ticket stubs, receipts – a collage of three lives there for you to piece together.

The story, told briefly, is that when the family moved, Sam had to move to a new high school. The house dad Terry inherited has a reputation in the neighbourhood as the “psycho house” because the elderly uncle from whom they inherited it was not liked societally, and this reputation makes it hard t for Sam to make new friends. Until she meets Lonnie that is.

Lonnie is a “bad influence”. They start an anti-patriarchal Zine, shoplift, smoke, and generally do things that bored teens do. Despite singing in a punk band and being generally a ‘bad girl’, Lonnie plans on joining the army after school. The girls fall in love and when Lonnie is meant to deploy to basic training camp, she can’t do it – she and Sam pack Sam’s car with as much as they can and drive off together into the sunset, to find somewhere just for them.

On the peripherals of the swirling vortex of teenage angst are the parents. Jan and Terry are having problems. Terry’s writing career has been stalled for some time and he’s struggling in his day job. He’s become distant and as a result, Jan is unhappy. She reads intentions into a new colleague that don’t exist, looking to find a new kind of spark, but we learn that her crush is committed to his girlfriend from a wedding invitation on the fridge. The anniversary trip is actually a couple’s counselling retreat as they try to save their failing marriage. There are hints that Terry suffered some horrible trauma at the hands of his uncle as a child.

The root of the conflict in the game is that Sam is a lesbian – her teenage antics are by-the-by really. In a diary entry, she says to Katie “You’ve known, right? I mean, I’ve known since She-Ra.” We discover that whatever sister Katie thinks about Sam’s sexuality, their parents are not happy. They give Sam all the classic lines – “You haven’t met the right boy yet, it’s just a phase.” Sam intones that it’s going to be a very long phase. The parents dictate that Sam can no longer have her bedroom door closed when Lonnie is over. Sam is most upset that they do not respect her enough to know she knows her own mind and heart; surely a relatable feeling to so many.

The main theme of the game is homophobia, both overt and covert. While we never get into the territory of hate crimes and that kind of aggressive bigotry, Gone Home explores the kind of everyday at-home homophobia that queer people have to deal with, day in and day out. “It feels like every minute that I don’t spend with Lonnie, I spend worrying about them finding out about us,” discloses Sam in a diary entry. That kind of life, hiding who you are and understanding the possible ramifications of discovery, will be familiar to many people who went through a fraught period of self-discovery, especially in the 90s.

Sam also discusses the hypocrisy of Lonnie’s plan to join the army in an era of “don’t ask, don’t tell” and her frustration at Lonnie’s laissez-faire attitude in a diary narration. This is, to me, Gone Home’s major failing, and I don’t think it’s even fair to call it that, really. It strives to tell the minutia of someone’s life and existence in this world of societal homophobia, and it does so superbly – my complaint is that I want so much more about this topic, but doing that would make it a different game. Gone Home does what it wants to do exceptionally well – I don’t want to change it; I want other game makers to explore these topics that matter to me.

A key characteristic of any game that earns the sometimes-derisive title of ‘walking simulator’ is that there is no combat. There isn’t anything to fight in Gone Home, you don’t carry a weapon. However, I do think it would be disingenuous to say that there’s no violence in the game. It’s just not the sort of violence we’ve come to expect from games, no blood splatter or bombast. It’s an everyday sort of violence, mundane and insidious, the kind of violence that leads to two teenage girls running away rather than turning to their parents or any authority figures in their lives. The violence of sadness. This isn’t unique to Gone Home, but even more than a decade after its release it remains just as applicable.

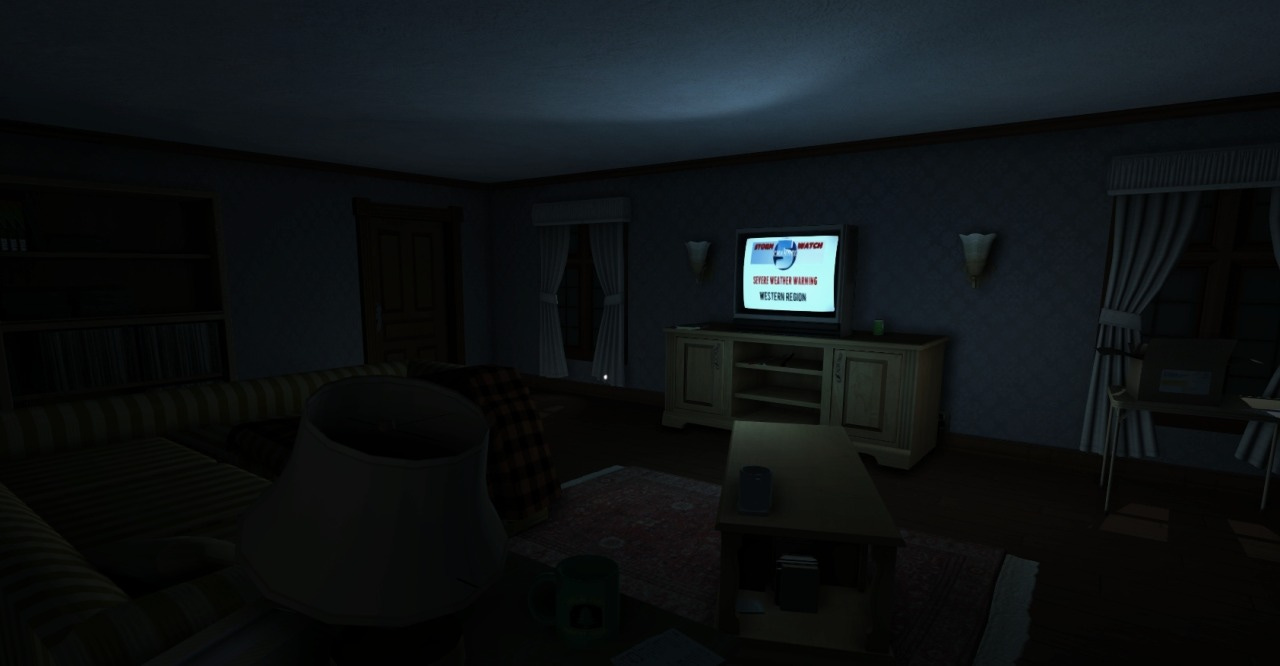

It also manages to subvert themes and tropes by masking itself as a horror game. Red hair dye looks like blood, thunder crashes, and the lighting is ominous. But it never follows through on the promise of terror. Whether you think the game ends with hope or sadness (or both), it eschews fear. But I played the game with my heart in my mouth, terrified of what I might find in the attic, terrified of what the outcome of Sam’s parents’ dismissive response to their daughter’s sexuality might be. This story can end in so many ways and while it’s not a horror story, not knowing which ending we’re building up to is scary. It also plays with the kind of inexplicable horror inherent in Katie’s ‘going home’ to a place that is never and will never truly be home to her – her family moved into this big old house when she was away in Europe and now ‘going home’ means going somewhere unfamiliar and alien. Of course, it could be argued that home is family, but the horror is compounded by the fact that none of them are here.

I want to talk about the second of the subversions I mentioned earlier. In the 1940s, Joseph Campbell popularised the theory of the monomyth, aka the Hero’s Journey. This idea suggests that at the heart of storytelling, there is one story wherein the hero of any tale leaves home, faces challenges, and comes home changed. The Lord of the Rings is a good example of this, and Tolkien explores deeply how Frodo will never be the same after his journey. Gone Home flips this on its head and Katie returns home seemingly unchanged to a world that is different to that which she left. What was is unrecoverable not due to the growth of the player character, but due to the very real changes of what she left behind. I don’t have an in-depth understanding of this literary device so this thought feels underdeveloped, but nonetheless worth mentioning. Maybe someone out there can run with this idea.

Gone Home invokes so much emotion in me. I grew up in the aftermath of Section 28 in Wales (I turned 13 the year it was abolished) and didn’t have the words to describe my identity until my 20s – it was even longer until I felt comfortable using them. I guess I was ‘lucky’ that as a bisexual/pansexual, I had mainly straight-passing relationships. But that doesn’t negate how it felt, the confusion and worry, the sense of what might happen if I was discovered. Gone Home brings it all back. It’s really hard to describe it as enjoyable to revisit, but it’s very easy to describe the game as important and to say that it is masterful in what it achieves.

I feel like it would be remiss of me not to mention the weird place Gone Home occupies in the gaming pantheon. It has been on the receiving end of a lot of negative attention, from people decrying it as “not really a game” to people who have no empathy for the experience it is trying to portray. It’s sad that when I went looking for analysis videos on the game, I wasn’t able to find any by queer theorists or even queer gamers – the YouTube feed was dominated by people decrying it as woke propaganda. It’s a small thing in the grand scheme of things, but it’s part of the trouble with the gaming industry as a whole – the loudest voices are not always the ones with the most nuanced opinions. If anyone knows of any good videos about Gone Home, please drop them in the comments.

There are a lot of pieces of media that strive to make the person engaging in it experience teenage nostalgia. There’s huge money in making people feel things about their youth. Gone Home does it so effortlessly. Anyone who grew up as a person on the edges of society will be transported. Naturally, it will hit home especially hard for anyone who had to hide who they were as a teen, but I recommend it wholeheartedly to everyone.

Game: Gone Home

Developer: The Fullbright Company (now just Fullbright)

Publisher: The Fullbright Company

Platforms: PC, mobile, PlayStation 4, Xbox One, Nintendo Switch

This was my first walking sim game and I was very drawn to it from start to finish. It opened the doors for me to things like “firewatch” and “vanishing of ethan carter”. Awesome write up! I love that you’re covering short indie classics

Looks interesting - wishlisted!