I’ve gone back and forth on how much, if any, of the story it would be okay for me to spoil in this review, and I think I’ve come down on the side of – this game came out in 2016, costs about £15, and only takes 4 hours to complete. If you want to avoid spoilers from 8-year-late reviews, you can. So I will be touching on story elements that are best experienced fresh – if you haven’t, here’s your encouragement to do so.

Firewatch is described by many as a walking simulator, but the more I think about it, the more I think that descriptor is lacking. Like, yes. You do walk around a lot. The whole game is a 3-month long hike. But that’s not really the point. It’s much more of a character experience, that’s where the heart of the game is. There are, by and large, two characters for the entire game. Henry, that’s you, and Delilah, your boss. You never get to meet Delilah, she’s a disembodied voice on your little walkie-talkie radio, but she’s part of the game in the way that someone would be part of your life if they were your only human contact for months on end.

The intro segment to Firewatch is like the writers at Campo Santo sat down and tried to figure out “how much mundane, human sadness can we cram into a three-minute text adventure?” It’s a lot, by the way. You go along with Henry as he meets Julia, courts her, and marries her. You see how plans can be derailed by other plans that seem just as important in the moment – Henry and Julia never have children, their careers get in the way. You hear about how chance doesn’t care what you want. Julia is diagnosed with early onset dementia after a series of truly upsetting to read-about incidents, and despite trying his best, Henry starts to drown under the ocean of responsibility. Julia’s parents whisk her away to Melbourne and Henry too escapes Boulder for the Shoshone National Park in Wyoming – escapes the home that was supposed to keep his family safe, the guilt that he could not care for her, the empty hole shaped like his wife.

It’s on this upsetting, sobering foundation that the whole game is built. Several times the dialogue options in-game give you the chance to acknowledge the truth hanging over you – “I shouldn’t be here,” says Henry. And you agree with him, how can you not? But it isn’t that simple. The game slowly, uncomfortably unpicks this – Henry knows he should be there, in Melbourne, with his dying wife. But he grapples with the pain of what they have lost, that she won’t recognise him. You know what the right thing to do is, but it’s impossible not to both empathise and sympathise with why Henry is doing the wrong thing. The question of what the player would do in the given circumstances never comes up – this is Henry’s story and this is a choice he has made.

This makes him a really interesting protagonist. Flawed, like the most fascinating ones are, and deeply, inescapably human. The two sides of the coin he’s holding are clearly visible. Characters in a lot of RPGs are a product of the choices made by the player (choices range between nice, nasty, sarcastic, and silent), or they are blank slates so players can project themselves into the world. Playing a defined character (in this case Henry, but maybe Aloy from Horizon: Zero Dawn, or Miles Morales in Spider-Man) is a very interesting part of gaming. They sit at an intersection that movies can’t reach, and that books can go deeper with inner monologues and internal worlds. Games put you inside a character in a very active way: you are performing the actions, making them speech choices, interacting with the world. It’s a very special medium.

One of the most interesting parts of this kind of characterisation is dialogue choices. You make a lot of dialogue choices in Firewatch, and while they will result in Worried Henry, or Funny Henry, or Quiet Henry, they are still all unmistakably Henry. It echoes real life in this way. You might have several things you could say in response to something, but you pick one and the conversation flows from there, like a river.

I think, having played it twice now, that Firewatch is a game about avoidance and the different ways that can resolve, or not. Henry’s avoidance of the life that won’t do what he wants leads him to Wyoming. Delilah repeatedly avoids, or talks about avoiding responsibility, resulting in tragedy. She tells the police that no one has seen the missing teenage girls (that Henry has most certainly seen) so she doesn’t have to deal with the fallout, she deflects questions about her personal life like she’s parrying swords, and she never told anyone about Brian Goodwin, despite the fact that he shouldn’t have been at the lookout with his dad Ned. She continues this throughout the entire game. She never tells Henry how she feels about him, she doesn’t even stay and face him when they are evacuated at the end of the game.

All these acts of avoidance, deflection, and evasion have their own outcomes. Sometimes it’s fine – the missing girls weren’t missing and Henry won’t get accused of murdering and hiding their bodies in the Shoshone. Sometimes, people are angry or disappointed – you can be either at the end when you learn she didn’t wait like she promised. Sometimes, there are tragic consequences – if Delilah had done her job and reported Brian Goodwin, he might not have died in a climbing accident. Sometimes, even if you run all the way from Colorado to Wyoming you can’t actually avoid the thing you’re running from – when Henry escapes the wildfire, where else can he go but back to the life he left behind?

From start to finish, Firewatch is a thing of beauty in so many ways. The voice acting is absolutely superb – Cissy Jones (Delilah) and Rich Sommer (Henry) work with a very restricted medium where no characters are ever actually shown on screen, but they convey emotion through the walkie talkie that’s more effective than many full acting performances. It would be remiss of me not to mention the art and how the game looks too. I have never been walking through a national park in the Rockies, but I feel like I have, thanks to Firewatch. Because the game takes place at various times of day they can play with colour palettes from bright, vibrant greens to vivid ochre and orange sunsets, to dark and mysterious nights. I took about 100 screenshots for this review where I will probably use three. The score fits perfectly, at times tranquil and gentle, at times urging you on to uncover the truth.

Firewatch is one of the games that drove me to create this blog, along with other favourites like Venba, and What Remains of Edith Finch. I had a lot of thoughts and feelings from revisiting the game, and I’d love to hear what you think about the game and its themes – am I right, or did I miss something glaring?

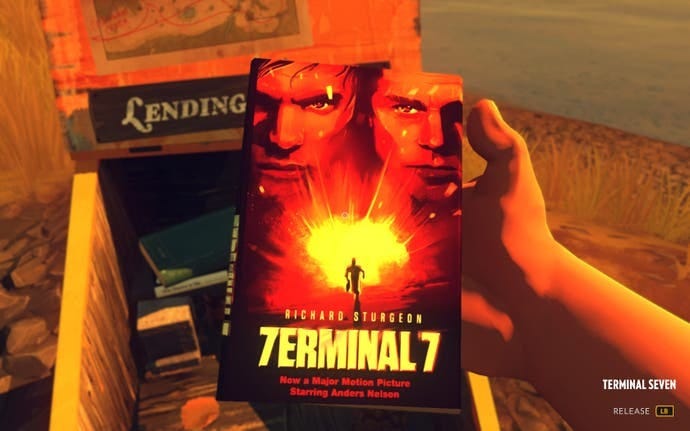

And before I go – Firewatch was developed by Campo Santo, a studio where Nels Anderson works. At the time of the game’s development, Nels ran a podcast called Terminal 7, about the card game Android: Netrunner. It came to an end in 2018 and was missed by the community at large and me specifically, so it was really neat to find a book in the game referencing the podcast. It made me smile – I’m so rarely on the inside of inside jokes, and this was one that warmed my heart.

I'm a simple man but I love it when creators reference their other works subtly in a project, and that makes me happy.

Sounds like a fascinating and sad game, and it's certainly beautiful. Maybe this is a game I'll have a better look at when I can handle a bit of external sadness.

I keep meaning to get this. Maybe it's on sale right now...