The Stanley Parable

When they got to the end of the review, the reader liked and shared the post.

I come to you today a little trepidatious. People love The Stanley Parable, and having a dissenting opinion to the popular consensus is tricky sometimes – I’m sure most people reading have been told at least once that their personal subjective opinion is wrong somehow, as if there’s a “correct” way to feel. In fact, I think that pushes against what The Stanley Parable is trying to accomplish.

Sorry, I’ve started out a little defensive, but bear with me. I am very much the sort of person who is “supposed” to like The Stanley Parable. I’m interested in narrative and form, how game mechanics can intersect with story, and the ludonarrative dissonance that occurs when they seem to work across each other. I’m also interested in media criticism and close examination and evaluation of the media we consume and how it is shaped, the expectations and norms it is constrained by, and the clever, subversive ways various things challenge those norms.

But the game just doesn’t hit for me. I thought it might be another case of me being an idiot when I was younger, but when I replayed it for QuickPlay, I still didn’t like it. Don’t get me wrong, I think it’s very clever. I’m sure many many words have been spent dissecting the game, extolling its virtues and teasing out all its snarky commentary on the medium of video games.

And boy howdy does it have a lot to say about the nature of video games and the relationship between player and creator. It’s much more of an exploratory artefact, a dissertation made into an interactive experience, than it is a game (though it’s indisputably a game still – we won’t tolerate any “walking simulators aren’t games” here).

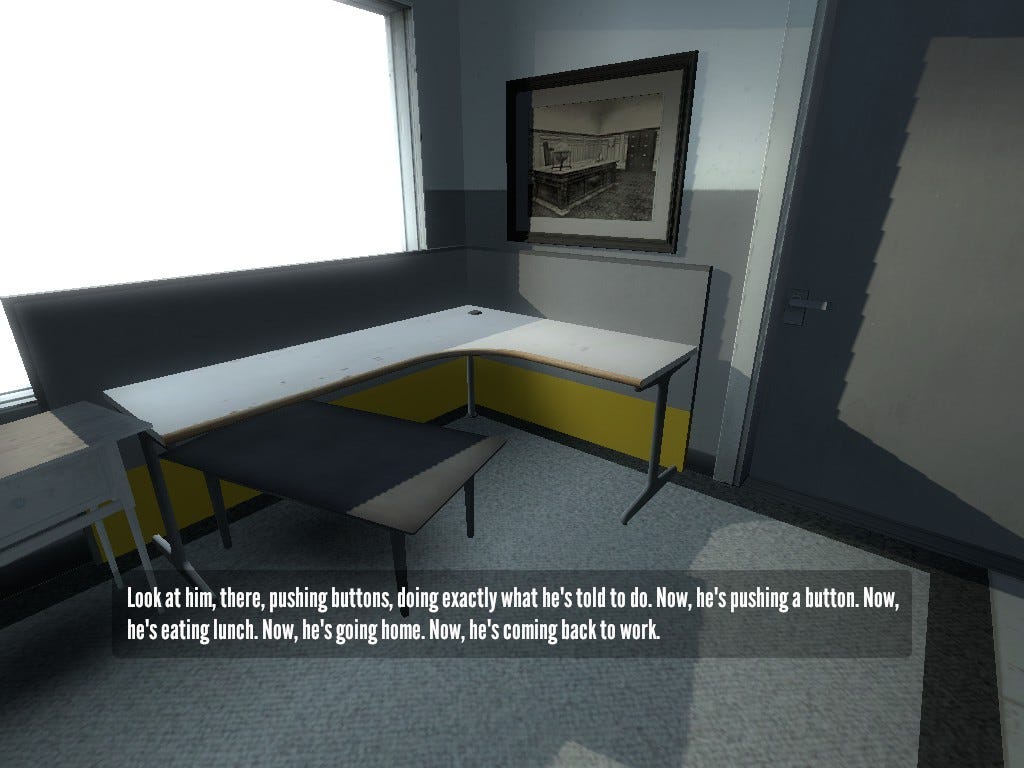

The Stanley Parable demands that you reckon with the antagonistic-yet-collaborative relationship between the player and the designer. It strips away the traditional trappings of a game, with theme and story and environmental design, and starkly zooms in on a single element of gaming – player choice and agency.

We can all acknowledge that video games are finite, constructed things which often try to masquerade as bastions of decision making, idolising the concept of choosing your own path. When we sit down and boot up a game, we have a mutual understanding with the designer that we won’t be able to do literally anything as players, but they will allow us to explore some options. (Ok, not all games are like this – some narrative games are at peace with their lack of player involvement aside from as a vessel to experience the story).

In most games, because a developer has to program every single thing and an artist has to bring it to life, there is an absolute upper limit on what the player can do. Doors are locked, slopes are too steep, or most egregiously, there are invisible walls and notes that “You cannot go that way.” It pervades across interactions with NPCs and items you can find and enemies you fight, and quests you do. This is something you just have to accept when you start playing a game. It might result in a bit of friction occasionally (such as when you don’t want to choose any of the available dialogue options, or you’re strolling down a road, and the game just tells you that you can’t continue).

Depending on the size and scope of the game, the quantity of options and the scope of the world will change. Something like Skyrim is huge, and not every choice will have any bearing on your experience. Do you go left or right? It probably doesn't matter that much because that single decision represents such a small percentage of your overall gameplay experience. On the other hand, smaller games such as Gone Home also have choices that don’t really matter, because they are inconsequential – you can go in whichever door you fancy first, because you’ll eventually visit every room in the house, and the order doesn’t matter. On the third hand (just go with me on this), there are games where certain choices are designed to matter – the Telltale games, for example. And then there’s the secret fourth hand, with games like Mass Effect that have some extremely impactful choices and some that don’t matter at all.

Choice is so important in games, and something that developers and designers have to consider every single outcome of. It’s such a core part of video games that Galactic Café has created a video game about it.

In The Stanley Parable, as you guide Stanley around his creepily empty office block, the omnipresent Narrator has something to say about everything you do. Whether you do as he tells you or utterly flout the directions, The Narrator responds. In fact, every single choice the player character makes elicits a response. It’s an exceptionally clever way to draw attention to the construct of video games and the usually inconsequential choices that layer up to create your individual experience with it.

The Narrator’s frustration with Stanley going and standing in the broom cupboard is a clear mirror of the inherent tension between the player’s desire to explore every nook and cranny and the designer’s desire to funnel them towards the plot that has been created and is the central focus of the game.

I think the game is extremely clever. My main issue with it is that it really knows it’s clever, to the point that I find the narrator smug and grating. This is very much a personal thing – most people find the game very funny. It’s not that I don’t think it is, more that I think the humour doesn’t land for me personally. As such, this game will never rank especially highly for me, despite the fact that I can appreciate on a craft and commentary level what it’s doing. I don’t think it could be any better than it is at what it’s extremely deliberately trying to do.

I think anyone with an interest in storytelling formats, particularly in games as a medium, should play The Stanley Parable. It’s extremely instructive, and you’ll learn a lot in the 5-7 hours it takes to experience all of the content. Most people think it’s hilarious on top of that, so don’t let my “eh” feelings about the game put you off.

Game: The Stanley Parable (just the base version, not the Ultra Deluxe one)

Developer: Galactic Cafe

Publisher: Galactic Cafe

Platforms: PC

Time to complete: 1-8 hours, depending on how many endings you want to find.

Don’t forget, if you want to support me but don’t want to subscribe through Substack (which I recognise is a very morally questionable platform), you can leave a one-off or recurring donation over at my Ko-fi page here :)

Agreed with the 'smug,' turned me off. watched a few playthroughs

Fascinating read, very insightful. I think I'm a sucker for things being clever even when they clearly know it, I'd probably enjoy this lol. Really interesting commentary on this though, very much enjoyed it